Some people think, or at least say they think, that politics doesn’t matter. Yet anyone who has been part of a successful campaign to change people’s lives for good knows better.

Such a campaign is the proper recognition of those who served our country in the Pacific Ocean in the 1950s when Britain undertook its first nuclear tests. Between 1952 and 1967 tens of thousands of servicemen participated in these atomic tests, though for decades afterwards their role was barely acknowledged. This lack of recognition was felt deeply by veterans who, along with their families, suffered a multitude of serious health conditions, clearly a result of radiation exposure.

I was inspired to be at the heart of all this by test veteran and Moulton resident Douglas Hearn, who became a good friend over our years campaigning together. Doug’s 13-year-old daughter Gill died from a rare form of cancer, which he believed was a result of his proximity to the bombs decades earlier. Many other veterans’ descendants suffered cancers, heart problems and miscarriages.

Sadly, Doug passed away before he saw the culmination of his efforts. After many years of hard work, in 2022 Boris Johnson agreed that veterans should receive long-awaited service medals. To date, just under 5,000 servicemen have received their medals.

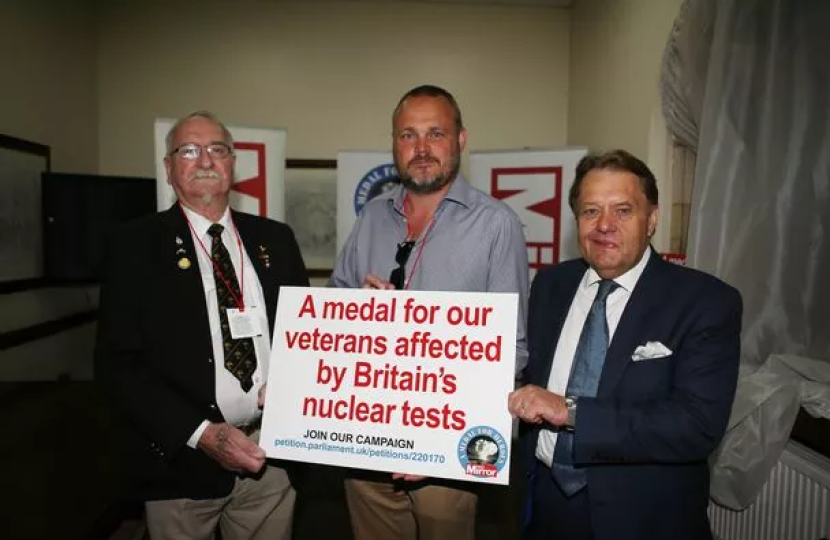

Nevertheless, our campaign hasn’t stopped there. Knowing that many who participated in the tests have yet to receive their medal, I am continuing to work across Parliament, with MPs of both main parties, to ensure veterans get the recognition they deserve. To this end, I met campaigners in Parliament just a few weeks ago. The Ministry of Defence is currently reviewing the criteria, so I am hopeful of a positive outcome.

Douglas Hearn also fought to uncover the full medical records of the veterans, to establish definitively what damage was done to those ordered to witness nearby nuclear explosions. To continue his work, I’ve been asking questions in Parliament and meeting Ministers as part of my push for the release of blood and urine data from tests on servicemen taken at the time of the tests. Despite commitments, the Atomic Weapons Establishment (AWE) seems reluctant to facilitate this.

So, in March, the test veterans launched legal action against the Ministry of Defence for their failure to release the records. The Government should either publish the files, so that individuals and families who have suffered can pursue claims, or simply provide a comprehensive package of compensation, as the UK is the only nuclear power that has not adequately compensated its test veterans, in the way that the US, France, Canada and Australia have.

Just last week I spoke on GB News to support their excellent campaign, highlighting the test veterans cause and backing their efforts to raise funds for the veterans’ upcoming annual reunion in Weston-Super-Mare.

My latest mission is to persuade the Government to build a dedicated memorial in London so that future generations will know the significance of our test veterans’ service and sacrifice. A precedent was set when the Bomber Command memorial was finally unveiled, in London’s Green Park, in 2012.

Our campaigning efforts are driven by recognition that we owe so much to those who have gone before us and to those still living with the effects of what they witnessed. Britain’s nuclear test veterans deserve nothing less than justice.